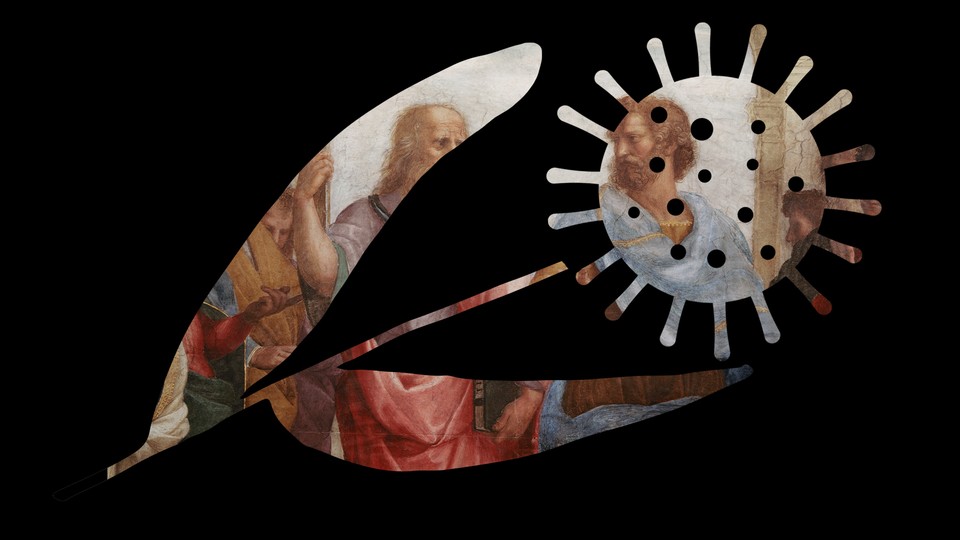

Preparing Your Mind for Uncertain Times

What ancient philosophers can teach us about embracing the unknown

This is a time of questions without answers. Will I get infected? When will there be a vaccine? Is my job secure? When will life be normal again? The experts may have guesses, or estimates, for some of these quandaries but there is no certainty, and this drives us nuts.

Humans abhor uncertainty, and will do just about anything to avoid it, even choosing a known bad outcome over an unknown but possibly good one. In one British study participants experienced greater stress when they had a 50 percent chance of receiving an electric shock than when they had a 100 percent chance. Intolerance for uncertainty puts people at greater risk for ailments such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

We take it as a given that uncertainty is always bad and, conversely, that certitude is always good. Yet ancient philosophy, as well as a growing body of scientific evidence, suggests otherwise. Uncertainty need not hobble us, and “in the right form and in the right amount, it’s actually a great pleasure,” says Daniel Gilbert, a psychology professor at Harvard.

We engage in certain activities—such as watching thrillers or reading mysteries—precisely because the outcome is uncertain. Or, say you receive a note from a secret admirer. The mystery of who sent it, Gilbert says, yields “the kind of uncertainty you would find delicious and delightful.” Yet we remain largely oblivious to our own love of pleasant—call it benign—uncertainty. Gilbert and his colleagues have found that even though uncertainty about a positive event prolongs people’s pleasure, we’re generally convinced that we’ll be happiest when all uncertainty is eliminated.

What about the darker kind of uncertainty, the kind many of us are facing now? Not only the immediate suffering of illness and job loss caused by the pandemic, but its open-ended nature. We don’t know when it will end. You might have noticed that this kind of uncertainty—let’s call it malign uncertainty—tends to make bad moods worse. But, again, this is only a tendency, not a foregone conclusion. We are not fated to suffer when faced with malign uncertainty. We have a choice.

In my experience, there are two ways to solve the “problem” of the unknown: by decreasing the amount of perceived risk or by increasing our tolerance for uncertainty. Most of us focus almost exclusively on the former. Many philosophers think this is a mistake.

Philosophers have wrestled with uncertainty and impermanence since at least the time of the ancient Greeks. Stoicism, a philosophy that flourished in the third century B.C. in Athens, is especially well suited for helping people cope with uncertainty. And for good reason: The Stoics lived during particularly unsettled times. Athens had lost much of its independence as a city-state, and the death of Alexander the Great several years earlier had left a power vacuum in the region. The old order had collapsed and a new one had yet to take its place.

Much of life lies beyond our control, Stoics believe, but we do control what matters most: our opinions, impulses, desires, and aversions. Our mental and emotional states. “Change what you can, accept what you cannot” sums up the Stoic creed. Master this skill, they say, and you will be “invincible.” This isn’t easy, the Stoics concede, but it is possible. Accepting the uncertainty inherent in life—particularly pandemic life—is better than fighting a constant battle against it, one we are bound to lose, the Stoics would say.

There’s a scene in the movie Lawrence of Arabia where Lawrence, played by Peter O’Toole, calmly extinguishes a match between his thumb and his forefinger. A fellow officer tries it himself, and squeals in pain.

“Oh! It damn well hurts,” he says.

“Certainly it hurts,” Lawrence replies.

“Well, what’s the trick, then?”

“The trick,” Lawrence says, “is not minding that it hurts.”

Lawrence’s response is pure Stoic. Sure, he felt the pain, yet it remained a sensation, a reflex. It never metastasized into panic. Lawrence didn’t mind the pain, in the literal sense of the word: He didn’t allow his mind to dwell on, and amplify, what his body had felt.

Likewise, the pandemic has hijacked the circumstances of our lives—that’s the reality we can’t avoid. But our minds and our reactions are still our own.

To show the power of mindset, Stoics use the metaphor of a cylinder rolling down a hill. Gravity ensures the cylinder will start rolling, but its shape determines how smoothly and quickly it rolls. We can’t control the hill, or gravity, but we can control the shape of our cylinder, the state of our minds.

For instance, let’s say you find yourself, like many parents, working from home while caring for a young child. Those facts represent the hill; they are immovable. What you can move is your attitude. It needn’t be a momentous shift either—we can’t all be Mother Teresa—but a subtle realignment from resistance to, if not total acceptance, at least tolerance.

The ability to tolerate uncertainty can bring great rewards. Uncertainty, after all, drives the quest for knowledge. The best scientists know this intuitively, and are willing to live with unknowns as they explore new frontiers. “I don’t have to know an answer,” the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman said. “I don’t feel frightened not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose.” Tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity are also linked with greater creative thinking, as several studies have found. The English Romantic poet John Keats introduced the term negative capability to describe a similar phenomenon. Writing to his brothers in 1817, he posited that writers are at their most creative when “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Japanese philosophers go a step further. Don’t merely tolerate uncertainty and its close cousin impermanence, they counsel; celebrate it. “The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty,” wrote Yoshida Kenkō, a 14th-century Buddhist monk.

Consider the sakura, or cherry blossom. The trees are famously fleeting. They bloom for only a week or two, and then the petals are gone. Other flowers—plum blossoms, for instance—last considerably longer. Why go to such great lengths to cultivate something as fragile as the cherry blossom?

Because “beauty lies in its own vanishing,” says Donald Richie in his book A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics. Life is ephemeral. Everything we know and love will one day cease to exist, ourselves included. That is life’s one certainty. The cherry blossom is lovely not despite its transience but because of it. This has always been the case. The pandemic has driven home our own transience. And while it may be too much to ask to celebrate this truth under such dire circumstances, we can learn to tolerate the unknown, and perhaps even catch glimpses of the beauty underlying life’s uncertainties.